Ever heard of Frederick Blomberg, the ‘secret son' of King George III? Not many people have. Rosalind Freeborn has researched the life of this little-known figure from Georgian royal history and pieced together his story in a lively and readable novel. Based on true events and real people, Prince George and Master Frederick reveals what happened to this ‘shadow prince' and the significance of his role as friend and close confidante to his half-brother, Prince George, future regent and King George IV.

My interest in Frederick Blomberg took many years to develop. When I was a child, my grandmother used to say, very grandly, that her family had a connection with King George III. This had always amused and intrigued me but, when I was 22, I sat down with her and asked for more details about the story. It was a scrambled and fragmentary tale but the gist of it was: King George III, as a young man, liked roaming the countryside and visiting farms. He fell in love with a farmer's daughter, had an illegitimate child with her and, to prevent a scandal and get the girl out of trouble, had her marry his equerry and best friend, Major William Blomberg. The child was given a name: Frederick William Blomberg.

So far, so straight-forward. Royal history is full of ‘accidental' children, some of whom are acknowledged, supported and live at the edge of royal life. But for Frederick Blomberg the story was very different. Alerted by a sensational ghost story which circulated in the mid-1760s, King George III and Queen Charlotte heard that the apparition of Major Blomberg (who died on active service in the Caribbean) appeared to his commanding officers imploring them to seek out the orphan child of his secret marriage, establish he was alive and well, and to tell the king.

On returning to England, the officers visited the address given by the ghost, duly found the child - a boy of nearly four years old - as well as a ‘red morocco box' containing documents relating to his Blomberg inheritance; a valuable estate in Yorkshire. They told the king and, to their credit, the royal couple adopted young Frederick, a child they had never seen before. They absorbed him into the royal household at Richmond Palace and brought him up as a prince. He became a playmate for the then three-year-old Prince George, infant Prince Frederick (future Duke of York) and newly-born Prince William (future King William IV).

Young Frederick Blomberg grew up with the royal children, was educated with them and, despite the curiosity surrounding his origins, seems to have been close to his adopted family. As the royal nursery became crowded with children (King George III and Queen Charlotte had 15 children!), Frederick and his brothers were removed from Richmond Palace to continue their education at Kew – the red-brick mansion situated in Kew Gardens– renamed the ‘Prince's House'. The King then paid for Frederick to study Divinity at St John's College, Cambridge. Once he had been ordained as a reverend at Ely Cathedral in 1784, the King granted granted Frederick the lucrative vicarage of Shepton Mallet in Somerset and, subsequently, vicarages at Bradford on Avon and Banwell. He was regarded in clerical circles as an ‘unashamed pluralist', accepting several livings at the same time: pocketing the salary and the vicarage or rectory that went with it, and appointing curates to do the work.

Reverend Frederick Blomberg was also given the role of chaplain to the royal family at Windsor and private secretary to Prince George, the Prince of Wales. So, far from finding himself buried in the countryside as a rural clergyman, Blomberg had been given a series of prominent vicarages and was now back with his royal family. In his new role as spiritual adviser, friend and family member, Frederick must have been a reliable and useful person to have at court especially during King George III's terrifying bouts of madness which threw the monarchy into chaos.

Frederick's seemingly equable personality and stable lifestyle was in stark contrast to that of Prince George, who was a greedy, self-serving and demanding spendthrift with little concern for the etiquette or responsibilities of royal life. However, studying the newspapers of the day, I was struck by how often the two men could be found in the same room together, at royal events or soirees, and frequently playing violin or cello duets. Clearly the two young men were both excellent musicians and took pleasure in the opportunity to play together.

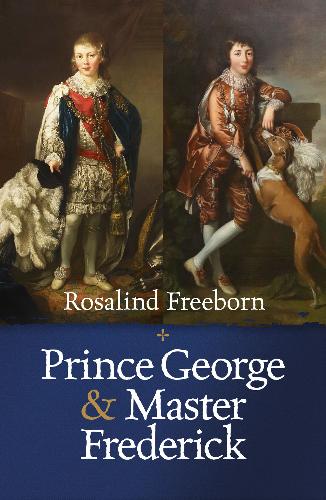

During my research for the book I was delighted to track down a spectacular portrait of Frederick Blomberg by the court artist Richard Brompton. It is a companion piece to a portrait of Prince George and Prince Frederick which currently hang on the wall of the 1844 Room at Buckingham Palace. Blomberg's portrait must have been gifted to him by the Prince Regent, probably when Queen Charlotte died. I'm delighted that the two paintings of Prince George and Master Frederick feature on the jacket of my book. Contemporary accounts frequently reference the boys' very striking likeness.

Frederick Blomberg remained in close contact with the Royal Family all his life. Apart from his particular friendship with Prince George he appears to have been the ‘go to' cleric for family weddings. In 1818, at Kew Palace, he conducted the marriage of his younger ‘half-brother' Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, to Victoria Louise of Saxe-Coburg–Saalfeld and, right at the end of his life, Reverend Blomberg was chaplain to their daughter when she became Queen Victoria.

I found another really important visual clue when conducting my research. In 1769, Queen Charlotte commissioned portraits of all her family from the court artist, Hugh Douglas Hamilton, including seven-year-old Frederick Blomberg. That little portrait must have eventually found its way into Blomberg's hands, probably after Queen Charlotte's death, and was taken to Blomberg's Yorkshire estate, Kirby Misperton, near Malton. It hung on the wall of his home until his death in 1847, stayed put through two subsequent owners and was there in 1900 when my grandmother's father, James Robert Twentyman, bought the estate for his family. He was an engineer from Durham who went out to China to make his fortune in shipping and built the docks in Shanghai. My grandmother grew up looking at this portrait and assumed he must be a relation but, as I have established, it was the property which provided the link. My family is not related to Frederick Blomberg. He, and his wife Maria, whom he married in Bath in 1787 remained together until Frederick's death, but they had no children. Blomberg's wealth was inherited by Anna Newbery, Maria's niece.

Last year, I was delighted to learn that the portrait my grandmother had grown up with was purchased by King Charles III for the Royal Collection Trust. I went to see it, now kept safely in the Print Room at Windsor Castle, along with the other portraits by Hamilton of his step-brothers. It pleases me to know that Frederick Blomberg is back with his family.

Prince George & Master Frederick by Rosalind Freeborn will be published by Alliance Publishing Press on 30th January. Price £15. It's available in print, on Kindle and on Audible from Amazon and bookshops.

PURCHASE FROM AMAZON NOW - https://amzn.to/4hwaKkX

ISBN: 9781838259853

There's more information on the author website: https://www.rosalind-freeborn.com/#/